Blog

Sharpening our research practice

First published June 14th 2018, on the OVO Tech blog

—

What sort of User Research practice do we want to cultivate?

We’re building up our User Research practice at OVO. Over the last few months our user research practice has grown, both in people joining the team and the methods that we are utilising. During this time of growth we started to ask ourselves the question ‘What sort of User Research Practice do we want to cultivate?’ As a team we decided that we wanted to acknowledge that we can refine our practice so that we:

are open about the biases and limitations in our research

use multiple research methods to help us understand user needs

respect our participants’ realities

Living up to these values means being the sort of team that takes the time out to practice our craft, so that we become more deliberate in our practice. As a team we are already exploring user needs through depth interviews, moderated and unmoderated usability testing and analysing our analytics. But there are limitations in only using these methods, and they don’t let us respect our participants’ realities.

Learning to observe

User research focuses on understanding people's behaviours and needs, through this we can learn what we should be designing and how. Sounds simple, right?! Afraid not. People are complicated, it's difficult to really understand how people do things and why. We can ask people how they do things and sometimes that works especially if we’re looking to learn about their own understanding of a thing. However as I said people are complicated and we can’t always articulate our behaviours.

To milk an overused example, imagine if I were to ask you how you make a cup of tea. You might start to tell me the steps you take, fill the kettle, boil, grab a mug etc. However, you might not tell me that you get distracted when boiling the kettle and have to reboil it. Or you don’t have many teaspoons so you pour a “teaspoons worth” of sugar into your mug. Not unusual, but you probably wouldn’t describe these aspects because you want to tell me a good story. However, these insights could lead to a kettle that whistles when it’s boiled, or a container that pours exactly a teaspoons worth of sugar every time.

Observation can help us understand many things including how people interact with their worlds. By observing their environments, we can capture the interactions between people and space. Further yet, by observing we begin to spot patterns that help us explain some of the complexities of being human: something we sometimes call culture, sometimes we call religion, and sometimes it's hard to put into words at all.

The patterns that emerge out of observation are essential not only to understanding a little bit more about life but also to design.

Setting ourselves the task of practicing observation

We set ourselves the goal to practice an open ethnographic observation methodology. Since our focus was on practicing the skill, it was important to carve out a time and a place where we could focus on practicing the method rather than on a “valuable” answer. To ensure we stayed true to our goal we agreed on the following objectives:

Explore how an observational study is planned

Understand the ethical considerations needed for an observational study

Practice observation data collection

Practice the analysis of observational data

We want to study what happens in Cabot Circus at lunchtime

Getting to the point at which we could agree on research question taught us:

There can only be one subject in the study, having 2 subjects in the study would already begin to accept assumptions into the research

There are many factors that we need to consider in preparing to conduct observations

Factors to consider:

Weather. We actually planned to use the park near our office as the subject but there were some dull looking clouds encroaching above so we changed tack and focused on the covered Cabot Circus instead.

We might be asked what we’re doing. We needed to have our story straight on our reason for observing in a public space.

Someone might interact with us. If this were to happen, it might distract from observing but also this might be an observation in its own right.

Discipline. Really concentrating and observing a space can be difficult we needed to be aware if we had started to daydream

Illegal activity. This might take place and what would we do if we observed such an activity

Recording what we see. How would we keep a record of our observations so that we took as much as we could from observing but whilst also not missing any potential observations

Ethical considerations

Our usual practice when conducting user research is to ask for informed consent from our participants prior to the research taking place. However collecting informed consent from people in Cabot Circus would have been both impractical and would have had an effect on the observations. The Social Research Association (SRA) warn of the difficulties of getting consent in observational studies. They offer 2 alternatives, gaining consent after the observation has taken place or not gaining consent if the observation is taken in a public space and there is no visible reluctance from participants.

Implied consent is described as “Consent which is not expressly granted by a person but rather implicitly granted by a person’s actions and/or circumstances”. Since we were conducting our observations in a public space, we adopted the principle of implied consent and asked ourselves questions at each stage of the study to determine if it was ethical for the research to continue:

Are we identifying the people that we observe?

How will the data we collect be used? (Using vs Publishing)

How is our observing affecting/influencing/impacting people and their behaviours?

What we found out about the method

Location within the environment will affect what you observe. Whilst conducting the observation we all took slightly different positions in Cabot Circus, as a result we all had different stories to share when regrouped. This showed us that as the subject of our study was Cabot Circus through one single observation at one time of day we would not be in a place to answer our question. We would need to factor in the space within the environment and time in our analysis of the data so that we could be open about the biases and limitations.

There are no wrong things to record. As this was our first observation of this subject there was no wrong thing for us to record as each piece of information would help our understanding. The location affecting what we observed was apparent in our field notes. Whereas one location brought with it a high volume of traffic of people the notes recorded tended to capture patterns. In contrast another location that had a lower volume of people created field notes that were more intimate. Neither were wrong.

Expect to feel uncomfortable when you do observation. Apart from the ‘numb bum’ and lack of water the act of observing makes you feel more aware of people watching you also. As you’re observing you have a heightened sense of being observed which may be a feeling that decreases with practice. Additionally the act of recording notes on paper is somewhat unnatural in some circumstances so we experimented with taking notes in what felt to be a more natural way for that environment, such as taking notes on our mobile phone.

Observation might not lead to definitive answers, but it will invite more questions. Although we didn’t come away from the day with a definitive answer on what happens in Cabot Circus at lunchtime, we did come away with more understanding about the subject of cabot circus and many more questions than we had expected. In that sense observation, we felt, is a great tool to add to our practice to inform our hypotheses when designing.

Sharpening how we sharpen our practice

Observation certainly feels like a method that we can use to help give us a fuller picture of who our users are, and their wider contexts. Sharpening our practice is not a one time deal though. Our biggest takeaway is that taking the time out as a team to experiment with a research method is something that we value. It’s allowed us to develop our practice but importantly (as we’re embedded in our product teams) has given us the time to develop our team relationships further.

Participant Experience Discovery Findings

First published January 2018, on Medium

This blog post is the result of a People Thinking project with Nic Price

—

What’s it like to be a user research participant?

Participants have needs when they are in a research interview. The words we use to set the scene can affect the participant’s understanding of what is being asked. The method of gaining consent can affect the participant’s comfort which will impact on how much they may divulge. What is less clear is the impact that the whole journey of taking part in research can have on our chances of getting the best insights.

A hypothesis

Participants have needs when they take part in research, if we meet these needs then we will get good quality insights, however those needs are not being met as well as they could so as result insights aren’t as good as they could be. If we discover what it’s like to be a research participant then we will be able to identify how to better meet those needs.

Additionally user research is still misunderstood, if we promote understanding of what user research is within our project and product teams by communicating from a participants view we will increase overall quality of user research.

What did we do? (a.k.a Methodology)

We had one research question

“What is it like to be a user research participant?”

To answer this question we drew up a research plan that broke that question into four;

What do user research participants need and when?

What’s it like to be a participant in a user research interview?

Are these needs being met today, how and by who?

How might we better meet these needs, and what would happen if we did?

Our participants for this research were people who:

had been participants

recruit participants

conduct user research

People who had been participants

This was further broken down into

Why do you take part in research?

What influences you taking part in research?

How do you feel when you take part in research?

What do you understand to be happening during the research?

Do you ever walk away wishing you’d said something else?

We used these questions to design a discussion guide. We conducted 5 x 30 minute depth interviews over the phone with people who had taken part in user research in the last 3 months. Participants in these interviews received a £25 incentive via bank transfer (handled by the recruiter)

We then took themes from these interviews to design a survey. The survey was administered via survey monkey and emailed to a database of people who have signed up to take part, and have taken part, in User Research. it was open for a week and achieved a response rate of 903. Respondents to the survey were entered into a prize draw for 4 x £25 Amazon voucher (handled by the recruiter).

People who recruit participants

We conducted contextual inquiries with a recruitment organisation.

People who conduct User Research

We conducted 3 semi-structured interviews with people who have conducted user research. This helped form our discussion guide for participants but themes from these interviews did not directly form the findings.

Limitations

There are limitations in the research, all our interviews were conducted remotely and they were all recruited via the same recruiter. The survey was sent to a ready engaged database of people and was conducted digitally. By its very nature, all those that took part had been participants previously (Very meta).

What did we find out?

48% of participants wouldn’t take part in a piece of research over Skype (video call)

Conducting your research over video call will exclude those who don’t have the technical ability in which to use that channel. It’s also seen as a intrusive method as it involves seeing into the participants environment.

If the research topic is sensitive or emotive it maybe that a video call is less success as participants report they can’t express themselves as well or connect with the researcher. This is a familiar finding in other video call research, the theory of social presence describes the need for a good quality communication medium when communicating.

41% of participants wouldn’t take part in home visit research

Similarly to video call interviews, home visits are intrusive but also feel dangerous to the participant inviting a stranger into their home.

But it’s not just the awkwardness of having someone come to your house. We need to be aware of the living arrangements of the person. Do they live in a busy household or shared accommodation therefore having the interview at their home may be unfair on those others in the house.

The non-video call and non-home visit populations overlap, in places.

As can be seen from the reasons for not having a video call or home visit interview there is some overlap in the reasoning. However that doesn’t mean that these populations are the same. There is an overlap, approximately a third of those that said they wouldn’t take part in a Skype interview also said they wouldn’t take part in a house visit interview.

A significant amount participants dislike the focus group method

Focus groups are seen as “competitive, restrictive and shouty”. As a result 15% of participants don’t want to take part in them, but a significant amount of the survey rated it as a method they disliked when compared to other methods.

For those that take part in research to be heard and make a difference say that the focus group is not a method in which they can do this.

The more research you take part in the more positive you are about research methods and environments

We need to be cautious of this due to the limitations in the research, however people are positive about taking part in research. As a result they want to take part in further research. They tell their friends and family about this too which leads to more people taking part in research. From our sample 44% of participants had been referred on by a family/friend/colleague.

We need to be aware too of the blockers to taking part in research:

Logistics

Bad parking was often cited as a pain. Just planning the journey to the research session and the stress that incurs can block people from taking part, or taking part with their whole selves .

Health

Health conditions, physical or mental, create barriers to taking part in research, suffering from agoraphobia — a fear of situations that may make you feel helpless or embarrassed — can prevent a participant from getting to and taking art in research.

Work

Approximately a third of people work 9am — 5pm (the Dolly Parton shift). User Researchers form a large part of this group therefore research is likely to take part between 9am — 5pm which immediately biases against those working that short pattern.

1 in 5 participants think of something relevant to add to the research after taking part.

Most user research sessions last 60 minutes, keeping participants longer would lead to fatigue. However, answering questions that you didn’t expect in a time pressured manner can be difficult. Therefore participants continue to think about the research questions and think of something that they would of wanted to say after the session has ended. They could have provided more to the session with more time or with more preparation.

Linked in with this is a sense of not seeing the value my insights offered. Participants take part in research to make a difference but often don’t see the impact sharing their stories had. It doesn’t satisfy their reason for taking part, neither does it provide closure to the research journey.

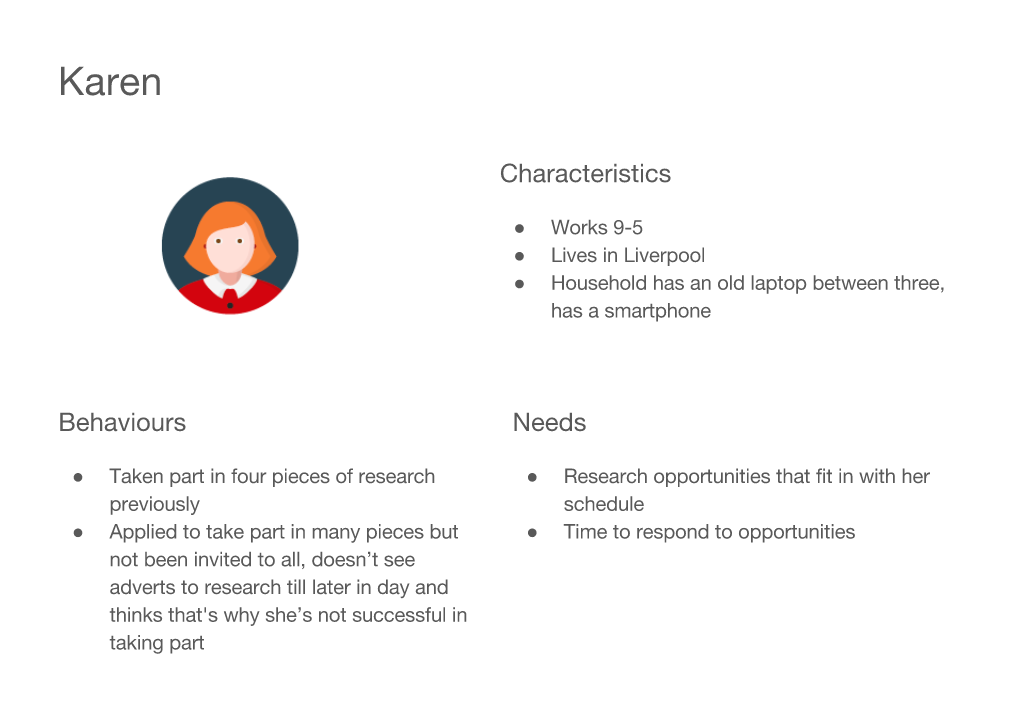

Meet Karen and Ron

We created personas to help us when we are designing our research opportunities.

Hello Karen

Hello Ron

So what does this all mean?

No research method is bad, this doesn’t mean you should stop doing Skype interviews. What it does mean is a reliance on a single method of research is bad and will bias your results.

Research doesn’t stop when the camera is off. Participants continue to think about research after the session. How might we capture those thoughts, additionally how might we conduct sessions which are less surprising and allow participants to prepare for them in a way that suits their needs.

Taking part in research is good, share that message to get others taking part in research.

We’ll be sharing shortly what the journey of a participant is like and the tasks they need to complete. In this we’ll explore further the pre-research nerves that participants feel and how that might be mitigated.

There are many questions that are left unanswered, some of those are:

What is the experience when participants are recruited via a different method/recruiter?

How do other user researchers conduct research? And how is this impacted by different sectors?

Why haven’t people taken part in research when offered the opportunity?

Participants have needs

First published January 2018, on Medium

This blog post is the result of a People Thinking project with Nic Price

—

What’s it like to be a user research participant?

This is a question we (Ben Cubbon and Nic Price) asked ourselves. And it became clear we didn’t know the answer.

So we kicked off a discovery to better understand the participant experience.

Our hypothesis was that by better understand the needs that participants have when taking part in research, we will be able to improve the design of our research, which will lead to better quality insights.

In addition to gaining better insights, we felt that by showing what research is like from the participant’s point of view we could promote a shared understanding of what research is across multi-disciplinary teams.

The participant journey is much more than just the research day.

To understand the research participant experience, we:

Conducted 5 in-depth interviews with participants

Spent a day observing a participant recruitment team

Surveyed 903 research participants

Through this we discovered the participant’s journey starts when they encounter an opportunity to take part in research. The journey doesn’t finish until days after the actual research session. You can read up on the needs we discovered.

Take part in a qualitative research interview task model

We shared the findings of this discovery at UX Bristol 2017. At the workshop we said we would be going into Alpha, and that time has now come.

Improving the participant experience

This is the beginning of taking the participant experience into Alpha where we will be testing out the following hypotheses that we came out of discovery with:

If we describe what user research is, and what the different research formats are, to potential participants then more people are likely to take part in research and feel less anxious when they do

If we provide a mechanism for participants and researchers to communicate after a research session has finished then better insights will be gathered by the research team, and participants will feel like their input has more value

If we inform user researchers of the biases and limitations that a research format can place on a participant then user research will use multiple formats when conducting research which will increase the diversity of participants and improve the quality of the insights for a project