Blog

Discovering how people use their energy usage data

First published October 30th 2018, on the OVO Tech blog

—

Discovery phase is often an overlooked phase in agile delivery. But they can be incredibly valuable.

Discovery is like an investigation, a small phase of time to understand the landscape of our users, the business, the technology and other external factors such as legislation. A good outcome of a discovery may be to not do anything, or it might be to set up a product team to proceed to alpha and testing some hypotheses generated by the phase.

We’re beginning to implement more discovery phases in the work we do. We’ve had good success following a leaner approach of jumping into hypotheses testing, however some problems need further investigation to begin to define good hypotheses.

Energy Usage graphs

A common pattern among energy suppliers to illustrate how much energy you’re using in a graph format.

But why are these useful? How are they used? What do people use them for? We were struggling to answer these questions. We had heard anecdotal stuff like “I like looking for spikes” but why is that important?

Ultimately we didn’t know what needs the graphs and the energy usage data were meeting.

We had started sketching ideas of how we might improve on how we display energy usage data. However we found that our conversations kept coming back to trying to improve the graph solely based on our opinions. This wasn’t helping us. Without knowing the user need(s) graphs meet, we couldn’t have an informed conversation about how we might improve the display of energy usage.

If we had attempted to start by researching our proposed sketches we would have struggled to design valid research. We needed to learn more about how graphs are used today in order to design contextual usability research to test our proposed ideas.

Very Disco

We saw this as an opportunity to conduct a discovery. We adopted the Government Digital Service (GDS) definition of a discovery. Before initiating this discovery I thought the aim of it would be something like “understand the needs people have when reading their energy usage data”. But it seems that the best discoveries are not centred around getting understanding but focused on being able to make a decision, reading these tips from Will Myddelton really helped frame how to kick off this phase.

A cross-disciplinary team got together for a 90 minute workshop to thrash out what we wanted to learn, what we didn’t want to learn and things we needed to find out.

This covered:

Learn about the tasks that users complete with the help of their usage graphs.

Understand what technical limitations there were.

Regulations we needed to be aware of.

We ended our workshop with this shared goal:

to understand the tasks our customers complete with their energy usage data so that we can decide if there is an opportunity for OVO to better help our customers.

Finding answers

Over the course of 3 weeks we:

Found answers to the business and technical questions we had.

We conducted depth interviews with OVO customers.

Held a conversation on the OVO forum.

Analysed the findings from our user research.

We intentionally sampled users who are using their usage data more frequently than average. We hypothesised that by doing so we would learn about the advanced tasks that are able to be completed with energy usage data. In understanding these more advanced needs, we hoped we’d learn how we could make them simpler so more users could benefit.

Because research is a team sport it wasn’t just me, the researcher, conducting these depth interviews and analysing the findings. I was joined by different team members to listen and take notes during the research sessions, and then joined again to conduct the analysis.

This is important, it’s more effective than any playback of research can be in getting a shared understanding of the user needs. It removes biases in the research analysis, and exposing team members to research has been proven to directly improve the experience that we deliver.

Tasks that are completed with energy usage data

As with any discovery, we were surprised with what we found. We spoke with people who were able to conduct a number of really sophisticated graphs with their energy usage data.

We heard how people used the graphs we provide to:

Check that there is nothing untoward happening in their house.

Control their monthly outgoings.

Decide if there are any actions they can take to use less energy.

Measure the impact a change made has had.

However, we also learnt that it’s not just about the graphs, we heard stories of how people collated their own data into alternative formats or paired it up with other sources of data, such as their solar panel outputs, to make more meaning from their usage.

Doing so helped people to:

Make a decision about when to use an appliance.

Get better informed estimates of what other deals would cost.

Tune household appliances to get to the optimum settings.

Ascertain whether something was worth investing in.

Decide if they should change an appliance.

Understanding that there are these range of tasks that can be, and need to be completed in the pursuit of energy efficiency is helping us define new hypotheses that we want to test. As suspected, it’s not really about making great graphs but actually about presenting the data in more usable ways.

More disco

Taking the time to really investigate an area to enable us to define better hypotheses is certainly something that we’ll be doing more of. By having an understanding of the tasks that users are completing with their energy usage data we are having better conversations around what improved usage data could be like. Before, we were too heavily centred around trying to improve the graphs which would have not had a great impact on meeting our user needs.

From this discovery we’ve learnt (maybe somewhat obviously) that trying to spin off a discovery on the side of the main focus of the product team is not the most effective way in which to get a shared understanding. We were left balancing this work alongside other competing team requirements. But this discovery has now given us a model on which to base and evolve the next one.

Sharpening our research practice

First published June 14th 2018, on the OVO Tech blog

—

What sort of User Research practice do we want to cultivate?

We’re building up our User Research practice at OVO. Over the last few months our user research practice has grown, both in people joining the team and the methods that we are utilising. During this time of growth we started to ask ourselves the question ‘What sort of User Research Practice do we want to cultivate?’ As a team we decided that we wanted to acknowledge that we can refine our practice so that we:

are open about the biases and limitations in our research

use multiple research methods to help us understand user needs

respect our participants’ realities

Living up to these values means being the sort of team that takes the time out to practice our craft, so that we become more deliberate in our practice. As a team we are already exploring user needs through depth interviews, moderated and unmoderated usability testing and analysing our analytics. But there are limitations in only using these methods, and they don’t let us respect our participants’ realities.

Learning to observe

User research focuses on understanding people's behaviours and needs, through this we can learn what we should be designing and how. Sounds simple, right?! Afraid not. People are complicated, it's difficult to really understand how people do things and why. We can ask people how they do things and sometimes that works especially if we’re looking to learn about their own understanding of a thing. However as I said people are complicated and we can’t always articulate our behaviours.

To milk an overused example, imagine if I were to ask you how you make a cup of tea. You might start to tell me the steps you take, fill the kettle, boil, grab a mug etc. However, you might not tell me that you get distracted when boiling the kettle and have to reboil it. Or you don’t have many teaspoons so you pour a “teaspoons worth” of sugar into your mug. Not unusual, but you probably wouldn’t describe these aspects because you want to tell me a good story. However, these insights could lead to a kettle that whistles when it’s boiled, or a container that pours exactly a teaspoons worth of sugar every time.

Observation can help us understand many things including how people interact with their worlds. By observing their environments, we can capture the interactions between people and space. Further yet, by observing we begin to spot patterns that help us explain some of the complexities of being human: something we sometimes call culture, sometimes we call religion, and sometimes it's hard to put into words at all.

The patterns that emerge out of observation are essential not only to understanding a little bit more about life but also to design.

Setting ourselves the task of practicing observation

We set ourselves the goal to practice an open ethnographic observation methodology. Since our focus was on practicing the skill, it was important to carve out a time and a place where we could focus on practicing the method rather than on a “valuable” answer. To ensure we stayed true to our goal we agreed on the following objectives:

Explore how an observational study is planned

Understand the ethical considerations needed for an observational study

Practice observation data collection

Practice the analysis of observational data

We want to study what happens in Cabot Circus at lunchtime

Getting to the point at which we could agree on research question taught us:

There can only be one subject in the study, having 2 subjects in the study would already begin to accept assumptions into the research

There are many factors that we need to consider in preparing to conduct observations

Factors to consider:

Weather. We actually planned to use the park near our office as the subject but there were some dull looking clouds encroaching above so we changed tack and focused on the covered Cabot Circus instead.

We might be asked what we’re doing. We needed to have our story straight on our reason for observing in a public space.

Someone might interact with us. If this were to happen, it might distract from observing but also this might be an observation in its own right.

Discipline. Really concentrating and observing a space can be difficult we needed to be aware if we had started to daydream

Illegal activity. This might take place and what would we do if we observed such an activity

Recording what we see. How would we keep a record of our observations so that we took as much as we could from observing but whilst also not missing any potential observations

Ethical considerations

Our usual practice when conducting user research is to ask for informed consent from our participants prior to the research taking place. However collecting informed consent from people in Cabot Circus would have been both impractical and would have had an effect on the observations. The Social Research Association (SRA) warn of the difficulties of getting consent in observational studies. They offer 2 alternatives, gaining consent after the observation has taken place or not gaining consent if the observation is taken in a public space and there is no visible reluctance from participants.

Implied consent is described as “Consent which is not expressly granted by a person but rather implicitly granted by a person’s actions and/or circumstances”. Since we were conducting our observations in a public space, we adopted the principle of implied consent and asked ourselves questions at each stage of the study to determine if it was ethical for the research to continue:

Are we identifying the people that we observe?

How will the data we collect be used? (Using vs Publishing)

How is our observing affecting/influencing/impacting people and their behaviours?

What we found out about the method

Location within the environment will affect what you observe. Whilst conducting the observation we all took slightly different positions in Cabot Circus, as a result we all had different stories to share when regrouped. This showed us that as the subject of our study was Cabot Circus through one single observation at one time of day we would not be in a place to answer our question. We would need to factor in the space within the environment and time in our analysis of the data so that we could be open about the biases and limitations.

There are no wrong things to record. As this was our first observation of this subject there was no wrong thing for us to record as each piece of information would help our understanding. The location affecting what we observed was apparent in our field notes. Whereas one location brought with it a high volume of traffic of people the notes recorded tended to capture patterns. In contrast another location that had a lower volume of people created field notes that were more intimate. Neither were wrong.

Expect to feel uncomfortable when you do observation. Apart from the ‘numb bum’ and lack of water the act of observing makes you feel more aware of people watching you also. As you’re observing you have a heightened sense of being observed which may be a feeling that decreases with practice. Additionally the act of recording notes on paper is somewhat unnatural in some circumstances so we experimented with taking notes in what felt to be a more natural way for that environment, such as taking notes on our mobile phone.

Observation might not lead to definitive answers, but it will invite more questions. Although we didn’t come away from the day with a definitive answer on what happens in Cabot Circus at lunchtime, we did come away with more understanding about the subject of cabot circus and many more questions than we had expected. In that sense observation, we felt, is a great tool to add to our practice to inform our hypotheses when designing.

Sharpening how we sharpen our practice

Observation certainly feels like a method that we can use to help give us a fuller picture of who our users are, and their wider contexts. Sharpening our practice is not a one time deal though. Our biggest takeaway is that taking the time out as a team to experiment with a research method is something that we value. It’s allowed us to develop our practice but importantly (as we’re embedded in our product teams) has given us the time to develop our team relationships further.

Participant Experience Discovery Findings

First published January 2018, on Medium

This blog post is the result of a People Thinking project with Nic Price

—

What’s it like to be a user research participant?

Participants have needs when they are in a research interview. The words we use to set the scene can affect the participant’s understanding of what is being asked. The method of gaining consent can affect the participant’s comfort which will impact on how much they may divulge. What is less clear is the impact that the whole journey of taking part in research can have on our chances of getting the best insights.

A hypothesis

Participants have needs when they take part in research, if we meet these needs then we will get good quality insights, however those needs are not being met as well as they could so as result insights aren’t as good as they could be. If we discover what it’s like to be a research participant then we will be able to identify how to better meet those needs.

Additionally user research is still misunderstood, if we promote understanding of what user research is within our project and product teams by communicating from a participants view we will increase overall quality of user research.

What did we do? (a.k.a Methodology)

We had one research question

“What is it like to be a user research participant?”

To answer this question we drew up a research plan that broke that question into four;

What do user research participants need and when?

What’s it like to be a participant in a user research interview?

Are these needs being met today, how and by who?

How might we better meet these needs, and what would happen if we did?

Our participants for this research were people who:

had been participants

recruit participants

conduct user research

People who had been participants

This was further broken down into

Why do you take part in research?

What influences you taking part in research?

How do you feel when you take part in research?

What do you understand to be happening during the research?

Do you ever walk away wishing you’d said something else?

We used these questions to design a discussion guide. We conducted 5 x 30 minute depth interviews over the phone with people who had taken part in user research in the last 3 months. Participants in these interviews received a £25 incentive via bank transfer (handled by the recruiter)

We then took themes from these interviews to design a survey. The survey was administered via survey monkey and emailed to a database of people who have signed up to take part, and have taken part, in User Research. it was open for a week and achieved a response rate of 903. Respondents to the survey were entered into a prize draw for 4 x £25 Amazon voucher (handled by the recruiter).

People who recruit participants

We conducted contextual inquiries with a recruitment organisation.

People who conduct User Research

We conducted 3 semi-structured interviews with people who have conducted user research. This helped form our discussion guide for participants but themes from these interviews did not directly form the findings.

Limitations

There are limitations in the research, all our interviews were conducted remotely and they were all recruited via the same recruiter. The survey was sent to a ready engaged database of people and was conducted digitally. By its very nature, all those that took part had been participants previously (Very meta).

What did we find out?

48% of participants wouldn’t take part in a piece of research over Skype (video call)

Conducting your research over video call will exclude those who don’t have the technical ability in which to use that channel. It’s also seen as a intrusive method as it involves seeing into the participants environment.

If the research topic is sensitive or emotive it maybe that a video call is less success as participants report they can’t express themselves as well or connect with the researcher. This is a familiar finding in other video call research, the theory of social presence describes the need for a good quality communication medium when communicating.

41% of participants wouldn’t take part in home visit research

Similarly to video call interviews, home visits are intrusive but also feel dangerous to the participant inviting a stranger into their home.

But it’s not just the awkwardness of having someone come to your house. We need to be aware of the living arrangements of the person. Do they live in a busy household or shared accommodation therefore having the interview at their home may be unfair on those others in the house.

The non-video call and non-home visit populations overlap, in places.

As can be seen from the reasons for not having a video call or home visit interview there is some overlap in the reasoning. However that doesn’t mean that these populations are the same. There is an overlap, approximately a third of those that said they wouldn’t take part in a Skype interview also said they wouldn’t take part in a house visit interview.

A significant amount participants dislike the focus group method

Focus groups are seen as “competitive, restrictive and shouty”. As a result 15% of participants don’t want to take part in them, but a significant amount of the survey rated it as a method they disliked when compared to other methods.

For those that take part in research to be heard and make a difference say that the focus group is not a method in which they can do this.

The more research you take part in the more positive you are about research methods and environments

We need to be cautious of this due to the limitations in the research, however people are positive about taking part in research. As a result they want to take part in further research. They tell their friends and family about this too which leads to more people taking part in research. From our sample 44% of participants had been referred on by a family/friend/colleague.

We need to be aware too of the blockers to taking part in research:

Logistics

Bad parking was often cited as a pain. Just planning the journey to the research session and the stress that incurs can block people from taking part, or taking part with their whole selves .

Health

Health conditions, physical or mental, create barriers to taking part in research, suffering from agoraphobia — a fear of situations that may make you feel helpless or embarrassed — can prevent a participant from getting to and taking art in research.

Work

Approximately a third of people work 9am — 5pm (the Dolly Parton shift). User Researchers form a large part of this group therefore research is likely to take part between 9am — 5pm which immediately biases against those working that short pattern.

1 in 5 participants think of something relevant to add to the research after taking part.

Most user research sessions last 60 minutes, keeping participants longer would lead to fatigue. However, answering questions that you didn’t expect in a time pressured manner can be difficult. Therefore participants continue to think about the research questions and think of something that they would of wanted to say after the session has ended. They could have provided more to the session with more time or with more preparation.

Linked in with this is a sense of not seeing the value my insights offered. Participants take part in research to make a difference but often don’t see the impact sharing their stories had. It doesn’t satisfy their reason for taking part, neither does it provide closure to the research journey.

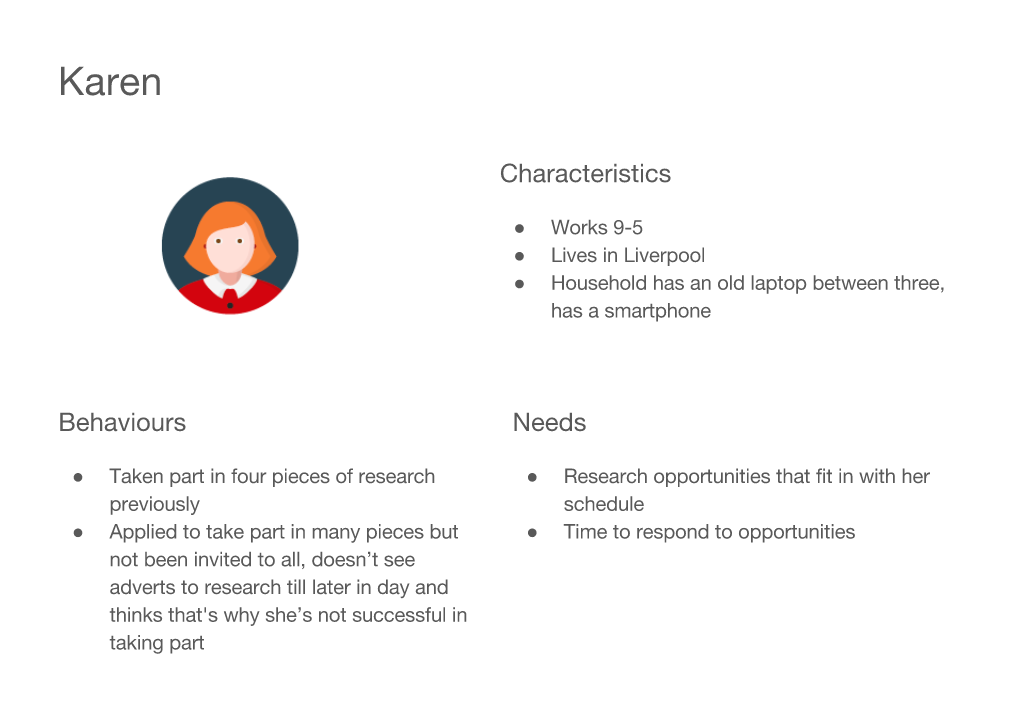

Meet Karen and Ron

We created personas to help us when we are designing our research opportunities.

Hello Karen

Hello Ron

So what does this all mean?

No research method is bad, this doesn’t mean you should stop doing Skype interviews. What it does mean is a reliance on a single method of research is bad and will bias your results.

Research doesn’t stop when the camera is off. Participants continue to think about research after the session. How might we capture those thoughts, additionally how might we conduct sessions which are less surprising and allow participants to prepare for them in a way that suits their needs.

Taking part in research is good, share that message to get others taking part in research.

We’ll be sharing shortly what the journey of a participant is like and the tasks they need to complete. In this we’ll explore further the pre-research nerves that participants feel and how that might be mitigated.

There are many questions that are left unanswered, some of those are:

What is the experience when participants are recruited via a different method/recruiter?

How do other user researchers conduct research? And how is this impacted by different sectors?

Why haven’t people taken part in research when offered the opportunity?

Participants have needs

First published January 2018, on Medium

This blog post is the result of a People Thinking project with Nic Price

—

What’s it like to be a user research participant?

This is a question we (Ben Cubbon and Nic Price) asked ourselves. And it became clear we didn’t know the answer.

So we kicked off a discovery to better understand the participant experience.

Our hypothesis was that by better understand the needs that participants have when taking part in research, we will be able to improve the design of our research, which will lead to better quality insights.

In addition to gaining better insights, we felt that by showing what research is like from the participant’s point of view we could promote a shared understanding of what research is across multi-disciplinary teams.

The participant journey is much more than just the research day.

To understand the research participant experience, we:

Conducted 5 in-depth interviews with participants

Spent a day observing a participant recruitment team

Surveyed 903 research participants

Through this we discovered the participant’s journey starts when they encounter an opportunity to take part in research. The journey doesn’t finish until days after the actual research session. You can read up on the needs we discovered.

Take part in a qualitative research interview task model

We shared the findings of this discovery at UX Bristol 2017. At the workshop we said we would be going into Alpha, and that time has now come.

Improving the participant experience

This is the beginning of taking the participant experience into Alpha where we will be testing out the following hypotheses that we came out of discovery with:

If we describe what user research is, and what the different research formats are, to potential participants then more people are likely to take part in research and feel less anxious when they do

If we provide a mechanism for participants and researchers to communicate after a research session has finished then better insights will be gathered by the research team, and participants will feel like their input has more value

If we inform user researchers of the biases and limitations that a research format can place on a participant then user research will use multiple formats when conducting research which will increase the diversity of participants and improve the quality of the insights for a project

Emotional and Mental Welfare for User Researchers

First published September 2017, on my Medium pages

—

User Researchers have an enviable role, there job is to empathise with users to understand their stories and then champion the user needs back to an organisation.

In government this position is even more humbling as we conduct primary research with participants that are retelling very sensitive stories. The services cover huge life events that are stressful, emotional and just difficult.

As user researchers we are humbled by those participants that are willing to tell us their stories, so that we can learn what we can do as organisations to do our bit in reducing the effort and stress that going through these services incurs.

As researchers we follow ethical and safeguarding guidelines to ensure that we look after the welfare of our participants. However, researching these highly sensitive and emotive topics can affect the mental state of the researcher facilitating the session. Spending the time empathising with our participants and reliving their experiences can impact researchers. It can remind us of our own previous experiences or ignite an emotional response that we weren’t expecting.

It is vital that we provide mechanisms to look after the welfare of researchers, by providing channels that allow researchers to vent their emotions and feelings about topics that they are understanding. There is only one argument that matters in this, and it’s one of morality.

Informally we sometimes debrief each other about the emotions that were experienced during the research. However there is no formal process in place in which to ensure the welfare of the emotional and mental state of researchers is maintained in a positive place. We haven’t normalised the action of seeking support in any of its possible forms. How do we really know if we are doing all we can to ensure that we are looking after the emotional and mental states of our researchers.

What we’re doing

Designing 3 tier approach to provide a process and support network to any researcher to protect their emotional and mental welfare.

This looks like :

A support community group. The aim of this would be to provide an open forum (open to researchers) where researchers could speak freely to the research community about research they have conducted and to discuss sensitive issues that have been raised. Primarily this forum would work on a asynchronous digital platform (Slack). Topics could also be discussed at Research community meetups.

Private liaison/buddying system. Researchers would put their name forwards to be buddies, this list would be open for access to the research community. The list would contain contact details, profile, previous experience and interests. Any researcher who is in need to talk to someone or debrief about a piece of research could contact any buddy from the list. The arrangements between the researcher and buddy would be decided by them. Guidance for how that chat could work would be provided.

Professional support. Signposting to professional support networks to discuss topics.

To achieve this we’re going to set up the network in two phases

Phase 1 — Get the infrastructure in place to be able to provide support

A private slack channel for all researchers

Terms of reference for being part of the Support network

Principles of support

Signposting to support options

Phase 2 — Raise awareness of support, normalise support and train staff to be part of giving support

Awareness training

Buddying system

Normalise support

Principles of Support

Talk about you, and your feelings

Getting support is normal

Listen carefully

It’s about you

Not a substitute for professional support

Just the first step

This is a first iteration at setting up a Welfare support network. We’re looking outwards to learn from other associations and organisations. I’m keen to speak with and learn from other similar setups.

We need to talk, about how we talk.

First published February 21st 2017, on my Medium pages

I spoke about this topic at UX Wales

—

Talking to the people who your use your services and products is great, I think we have got to a point where we all can agree on that. User research is essential. No longer do I find myself selling the need to speak with users. Now the conversation focuses on how this will be done. And how, is a conversation that we don’t have often enough.

In Interviewing Users the author Steve Portigal perfectly articulates the aspects of interviewing that are easily taken for granted. Elements such as writing (and delivering) the introduction of the research interview and the effect that can have on the rest of the interview, the data that is collected and fundamentally on the participant (who for the duration of the interview is under the care of the researcher).

“Let the participant know what to expect by giving a thumbnail outline of the process” Interviewing Users, Steve Portigal

This part of the interview cannot be underestimated. It sets the tone, lets the participant know what is going to happen and what is going to be covered. As a researcher we’re used to speaking to a range of people in labs, or at homes, with cameras on. But this isn’t an everyday occurrence for people. It’s not everyday you’re in an IKEA decked out studio in the city centre with cameras in the corner and some ominous looking one way mirror.

Remember we all agree that researching with the people who use our services is essential, right! This means that without people who want to take part in research we won’t be able to do our work. Conducting a research interview is a service to our participants and they have needs when then come to be interviewed. If we don’t set the scene right we’ll have uncomfortable participants with unmet participant needs. An uncomfortable feeling participant may close up and may not give you the whole story. If this happens you may not get to the root user need of your service. Our participants are not the subject of a test, they are the expert of your service and we’re privileged that they want to talk to us. They’re not being tested.

The introduction phase to an interview is crucial to the wellbeing of your participant and the data that you’re collecting from that interview. I know this, deep down somewhere. But I’ve never sat down and thought through why it is or how it should be phrased. But given it is a crucial factor to the interview we should look at how we write and deliver this section more. What effect is it having? What happens if I introduce the interview differently to my participants? These are topics we should be talking about as user researchers.

I could go on. Sitting down to read Steve’s book made me look and critique how I conduct interviews. The tone I adopt. The way I sit. The way I nod along. The way I ask questions. The way I construct follow up questions. These are all crucial. We know they are as researchers. But it feels like we have stopped talking about this. We’ve focused so much recently in Government at getting user research a seat at the table. But we have that seat now. Let’s make sure that the profession of user research continues to deserve that seat, and lets get more seats.

I’ve looked on in envy in the last few years at the design community. They’re an open community, they share their designs and workings in the open. This leaves them vulnerable to being poked and prodded, it starts conversations though. The outcome of this is hugely positive. The design becomes stronger. We too need to be open about how we conduct research. What method did we use, it’s not enough just to say we interviewed. How did you interview? How were the questions asked? The answers to those 2 questions could change the findings that come out of an interview. It’s not good enough just to say we spoke to some users and they said x so we should do it. We need to talk about how we talk with our users. We need to conduct good quality research because the services we are working on in Government matter, and the findings we bring back from research have an impact on what services we design.