Blog

Creating an accessibility workshop

First published December 18th 2019, on the OVO Tech blog

—

Background

OVO's vision is to "power human progress with clean and affordable energy for everyone". This means striving to build our digital products so that people of all abilities can use them. This year we celebrated our Accessibility Community of Interest’s 1st birthday. The group was started to raise awareness of the different needs that people have and how our product development decisions can include or exclude people. To achieve OVO's vision we need to mature our understanding and ability to make accessible products.

Identifying our needs

We used the liberating structures technique of 1-2-4-all at our accessibility community gathering to identify the barriers we, as product teams, faced in making our products more accessible.

We analysed the insights and identified themes that would help us become more accessible. We had an assumption that our colleagues would share our understanding of accessibility. Themes we identified demonstrated that we had to better share our current knowledge around tooling, guidelines and assistive technology. We identified specific needs such as how to use aria-live in different situations which we will revisit after addressing our foundational needs.

Developing a workshop

We hypothesised that a small group of us who come from a range of disciplines: front-end development, design and research, would be able to create a workshop that would meet the needs we'd discovered and increase our accessibility maturity.

We defined principles to guide the development of our workshop

more than 1 discipline should facilitate the workshop

more than discipline should benefit from the workshop

it's not a lecture, it should be practical

attendees should be able to put lessons into practice immediately

its a shared learning experience, for attendees and facilitators

These principles allowed us to break the workshop into chapters that we could each take responsibility for creating. We identified that our "Introduction to accessibility" workshop should cover:

What is accessibility

What is the rationale for accessibility

How do disabled people access digital products

What are the standards and guidelines for web accessibility

How can we test the accessibility of our products

The most common accessibility failures

Workshop alpha

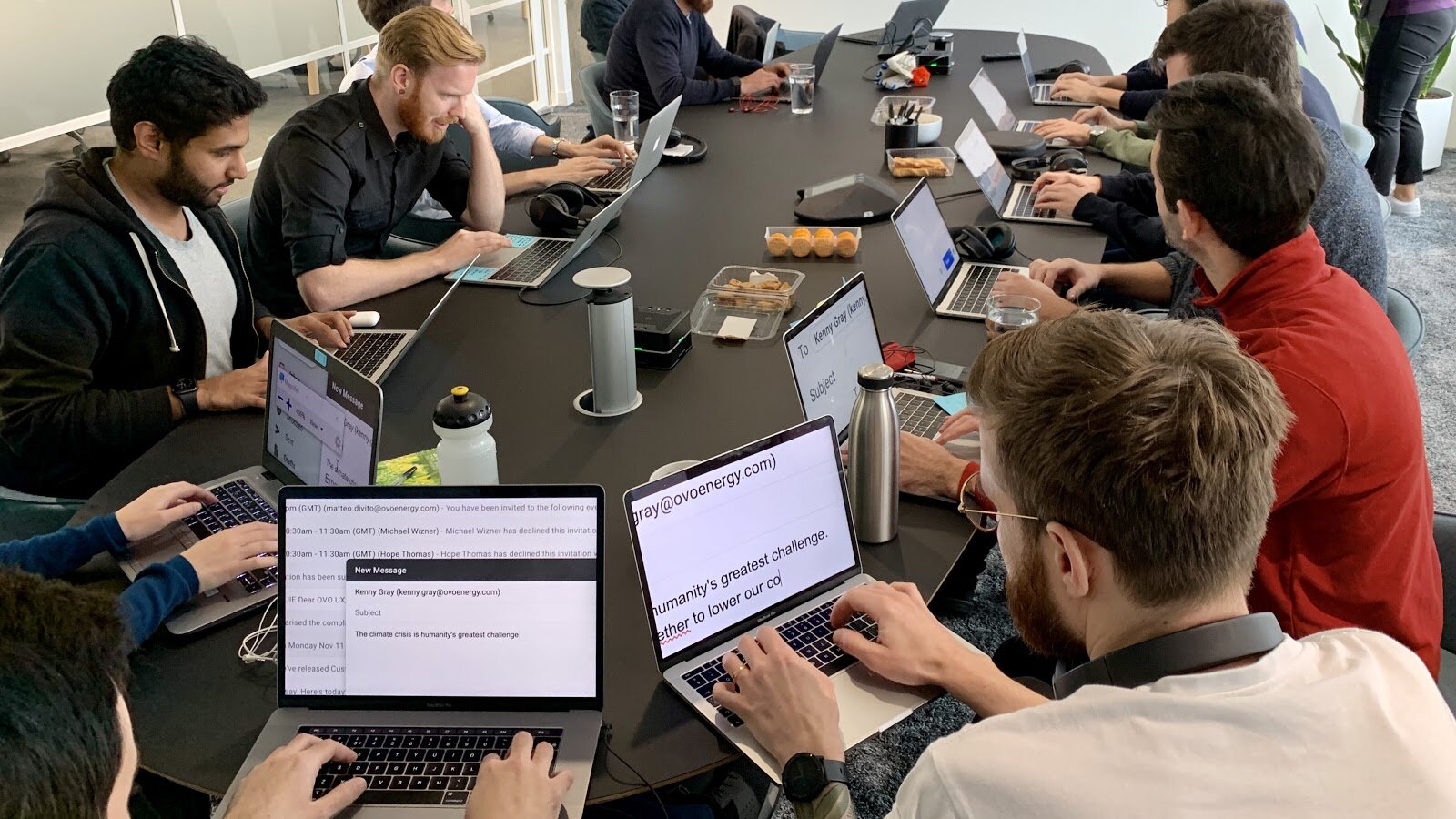

Our Digital Support Experience (DSE) team volunteered to be the first to take part in our workshop. This pilot provided an opportunity to learn if the workshop was informative, useful and fun. It also taught us about how to facilitate the workshop.

Thankfully the pilot was a success, we also learned a tremendous amount about how to conduct it.

The content was appropriate for everyone in a product team. In our pilot workshop we had a product managers, a few developers and designers. Having the whole product team present was powerful. It’s not very often that everyone can take a couple of hours out to learn together.

We should first practice how to use assistive technology and accessibility testing tools away from the product we work on every day. This allowed us to focus on learning how to use the tools and interpret the results, rather than assessing our products.

We need to provide set tasks or have goals to complete when using assistive technology. Without this purpose it’s hard to appreciate how the technology works or how difficult it might be to use it.

We should download accessibility testing tools one at a time and learn how to interpret the results together. Giving attention to one tool at a time allows for the group to have a better understanding on how to use them. Using time in the workshop to install tools like Accessibility Insights [link] was a great outcome.

Ask attendees to bring headphones. In our pilot we did not have headphones which created a very loud choir of the BBC headlines.

Workshop live

We have delivered the workshop on 3 more occasions, with 42 attendees, covering 8 product teams. We're continuing to refine the content and delivery of it.

We want the workshop to help increase our accessibility maturity from awareness to knowledge, so that we could make our products more accessible tomorrow than they are today. We're aware that we're not experts on accessibility but we're keen to share what we know to encourage incremental change. The early signs have been positive, so far we have observed the attendees of the workshops:

use the tools and assistive technology to conduct their own technical assessments to identify accessibility fixes to their products

help inform other product teams of accessibility shortcomings in their products

reprioritise an internal initiative to embed accessibility from the beginning

Sharpening our research practice

First published June 14th 2018, on the OVO Tech blog

—

What sort of User Research practice do we want to cultivate?

We’re building up our User Research practice at OVO. Over the last few months our user research practice has grown, both in people joining the team and the methods that we are utilising. During this time of growth we started to ask ourselves the question ‘What sort of User Research Practice do we want to cultivate?’ As a team we decided that we wanted to acknowledge that we can refine our practice so that we:

are open about the biases and limitations in our research

use multiple research methods to help us understand user needs

respect our participants’ realities

Living up to these values means being the sort of team that takes the time out to practice our craft, so that we become more deliberate in our practice. As a team we are already exploring user needs through depth interviews, moderated and unmoderated usability testing and analysing our analytics. But there are limitations in only using these methods, and they don’t let us respect our participants’ realities.

Learning to observe

User research focuses on understanding people's behaviours and needs, through this we can learn what we should be designing and how. Sounds simple, right?! Afraid not. People are complicated, it's difficult to really understand how people do things and why. We can ask people how they do things and sometimes that works especially if we’re looking to learn about their own understanding of a thing. However as I said people are complicated and we can’t always articulate our behaviours.

To milk an overused example, imagine if I were to ask you how you make a cup of tea. You might start to tell me the steps you take, fill the kettle, boil, grab a mug etc. However, you might not tell me that you get distracted when boiling the kettle and have to reboil it. Or you don’t have many teaspoons so you pour a “teaspoons worth” of sugar into your mug. Not unusual, but you probably wouldn’t describe these aspects because you want to tell me a good story. However, these insights could lead to a kettle that whistles when it’s boiled, or a container that pours exactly a teaspoons worth of sugar every time.

Observation can help us understand many things including how people interact with their worlds. By observing their environments, we can capture the interactions between people and space. Further yet, by observing we begin to spot patterns that help us explain some of the complexities of being human: something we sometimes call culture, sometimes we call religion, and sometimes it's hard to put into words at all.

The patterns that emerge out of observation are essential not only to understanding a little bit more about life but also to design.

Setting ourselves the task of practicing observation

We set ourselves the goal to practice an open ethnographic observation methodology. Since our focus was on practicing the skill, it was important to carve out a time and a place where we could focus on practicing the method rather than on a “valuable” answer. To ensure we stayed true to our goal we agreed on the following objectives:

Explore how an observational study is planned

Understand the ethical considerations needed for an observational study

Practice observation data collection

Practice the analysis of observational data

We want to study what happens in Cabot Circus at lunchtime

Getting to the point at which we could agree on research question taught us:

There can only be one subject in the study, having 2 subjects in the study would already begin to accept assumptions into the research

There are many factors that we need to consider in preparing to conduct observations

Factors to consider:

Weather. We actually planned to use the park near our office as the subject but there were some dull looking clouds encroaching above so we changed tack and focused on the covered Cabot Circus instead.

We might be asked what we’re doing. We needed to have our story straight on our reason for observing in a public space.

Someone might interact with us. If this were to happen, it might distract from observing but also this might be an observation in its own right.

Discipline. Really concentrating and observing a space can be difficult we needed to be aware if we had started to daydream

Illegal activity. This might take place and what would we do if we observed such an activity

Recording what we see. How would we keep a record of our observations so that we took as much as we could from observing but whilst also not missing any potential observations

Ethical considerations

Our usual practice when conducting user research is to ask for informed consent from our participants prior to the research taking place. However collecting informed consent from people in Cabot Circus would have been both impractical and would have had an effect on the observations. The Social Research Association (SRA) warn of the difficulties of getting consent in observational studies. They offer 2 alternatives, gaining consent after the observation has taken place or not gaining consent if the observation is taken in a public space and there is no visible reluctance from participants.

Implied consent is described as “Consent which is not expressly granted by a person but rather implicitly granted by a person’s actions and/or circumstances”. Since we were conducting our observations in a public space, we adopted the principle of implied consent and asked ourselves questions at each stage of the study to determine if it was ethical for the research to continue:

Are we identifying the people that we observe?

How will the data we collect be used? (Using vs Publishing)

How is our observing affecting/influencing/impacting people and their behaviours?

What we found out about the method

Location within the environment will affect what you observe. Whilst conducting the observation we all took slightly different positions in Cabot Circus, as a result we all had different stories to share when regrouped. This showed us that as the subject of our study was Cabot Circus through one single observation at one time of day we would not be in a place to answer our question. We would need to factor in the space within the environment and time in our analysis of the data so that we could be open about the biases and limitations.

There are no wrong things to record. As this was our first observation of this subject there was no wrong thing for us to record as each piece of information would help our understanding. The location affecting what we observed was apparent in our field notes. Whereas one location brought with it a high volume of traffic of people the notes recorded tended to capture patterns. In contrast another location that had a lower volume of people created field notes that were more intimate. Neither were wrong.

Expect to feel uncomfortable when you do observation. Apart from the ‘numb bum’ and lack of water the act of observing makes you feel more aware of people watching you also. As you’re observing you have a heightened sense of being observed which may be a feeling that decreases with practice. Additionally the act of recording notes on paper is somewhat unnatural in some circumstances so we experimented with taking notes in what felt to be a more natural way for that environment, such as taking notes on our mobile phone.

Observation might not lead to definitive answers, but it will invite more questions. Although we didn’t come away from the day with a definitive answer on what happens in Cabot Circus at lunchtime, we did come away with more understanding about the subject of cabot circus and many more questions than we had expected. In that sense observation, we felt, is a great tool to add to our practice to inform our hypotheses when designing.

Sharpening how we sharpen our practice

Observation certainly feels like a method that we can use to help give us a fuller picture of who our users are, and their wider contexts. Sharpening our practice is not a one time deal though. Our biggest takeaway is that taking the time out as a team to experiment with a research method is something that we value. It’s allowed us to develop our practice but importantly (as we’re embedded in our product teams) has given us the time to develop our team relationships further.